Here’s how Blackburn describes pragmatism:

You will be a pragmatist about an area of discourse if you pose a Carnapian external question: how does it come about that we go in for this kind of discourse and thought? What is the explanation of this bit of our language game? And then you offer an account of what we are up to in going in for this discourse, and the account eschews any use of the referring expressions of the discourse; any appeal to anything that a Quinian would identify as the values of the bound variables if the discourse is regimented; or any semantic or ontological attempt to ‘interpret’ the discourse in a domain, to find referents for its terms, or truth-makers for its sentences … Instead the explanation proceeds by talking in different terms of what is done by so talking. It offers a revelatory genealogy or anthropology or even a just-so story about how this mode of talking and thinking and practising might come about, given in terms of the functions it serves. Notice that it does not offer a classical reduction, finding truth-makers in other terms. It finds whatever plurality of functions it can lay its hands upon. [Simon Blackburn, Expressivism, Pragmatism and Representationalism: 75]

I'm interested in the claim often made by pragmatists, such as Simon Blackburn or Huw Price, that they are eschewing metaphysics, in contrast to platonists, fictionalists, error theorists and the like. Pragmatic accounts of a discourse provide a genealogy, or some consanguineous account, of why it is we go in for this way of talking and, as it may happen, this account may be metaphysically deflationary. So it may be that the motivation for talking about, say, mathematical objects, does not involve representing how things stand with a domain of mathematical objects. If there is some such story—if we can account for the uses of mathematical talk, without invoking mathematical objects—then we have an ontologically deflationary pragmatic account of mathematical discourse.

But so far, what’s been said about pragmatic accounts of mathematical discourse is open for the fictionalist to adopt. The difference between the fictionalist (who is apparently engaged in metaphysics) and the pragmatist (who apparently eschews metaphysics) is that the fictionalist claims that mathematical talk is, strictly speaking, false, whereas the pragmatist does not.

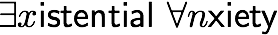

Fictionalists and pragmatists then agree in methodology: provide an account of the usefulness of mathematical (or moral, or possible worlds) discourse that makes the existence of mathematical (or moral, or modal) objects orthogonal to the practice. Their point of divergence is not methodological or ontological, but semantic: whether one opts for fictionalism or pragmatism depends on what one takes the meaning of existential quantification to be. Here, the pragmatist reads the pragmatic purpose of quantification over mathematical objects back into the semantics of quantification over mathematical objects, and the fictionalist does not. A truism: people can engage in ontological disputes. There is something at stake between someone who claims that the Higgs boson exists and someone who claims that it does not, or between someone who claims that God exists and someone who claims that he does not. The interlocutors in these debates are in disagreement over what the world is like. So, sometimes at least, quantificational talk is used to express disagreements about what the world is like. Ultimately then, the difference between the fictionalist and the pragmatist lies in what they take the meaning of existential quantification to be. Fictionalists take existential quantification to be univocal: it always expresses claims about what the world is like. Pragmatists (are committed to) taking existential quantification to be multivocal: within discourses whose purpose is to describe the world existential quantification expresses claims about what the world is like; within discourses whose purpose is not to describe the world, existential quantification does not express claims about what the world is like. (Note that the point of divergence is not, or need not be, over semantic minimalism. The person engaged in metaphysics need not couch what he is doing in terms of finding truth-makers or referents to be relata in substantive relations of truth or reference to given sentences; he can simply couch what she is doing in terms of whether such and such objects exist. Hartry Field is a case in point.)

The take-away claim: whether one gets to eschew metaphysics depends on whether existential quantification is univocal or multivocal.