- Cognition is (distinguished as) that which is properly subject to certain kinds of normative assessment. (The "mark of the mental" is that it is subject to certain kinds of normative assessment.)

- If cognizers did not have libertarian free will then cognition would not be properly subject to those kinds of normative assessment.

- Cognizers have libertarian free will.

- Human persons are cognizers.

- Therefore, human persons have libertarian free will.

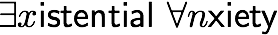

The idea behind the 1 is that persons are responsible for their beliefs. If someone believes that P, that if P then Q, and that not Q, then that person has transgressed in some sense. Cognition is bound by rules, not in a nomic sense (these rules can be violated), but in a normative sense (one ought not to violate these rules). Sapients are distinguished from non-sapients in precisely this way: one ought not to criticize a system on the grounds that its entropy is increasing, but one can criticize a person on the grounds that his beliefs are inconsistent.

The motivation for 2 runs along the same lines that are usually given for holding that moral responsibility requires libertarian free will: namely that if determinism is true then one's acts are consequences of laws of nature and past events, but (i) we are not responsible for what laws of nature and past events obtain, and hence (ii) we are not responsible for the consequences of what laws of nature and past events obtain (including the subset of those consequences that contains our actions).

Van Inwagen famously argues for libertarian free will on the grounds that we have moral responsibilities, but it seems to me that the argument from cognition has a dialectical advantage over the moral one. Philosophers are largely willing to reject the existence of moral truths if they take this to be incompatible with their metaphysical commitments. I doubt that philosophers generally would be as willing to give up cognition on those grounds.

I take it that 2 is the controversial premise here, but it seems prima facie plausible to me.